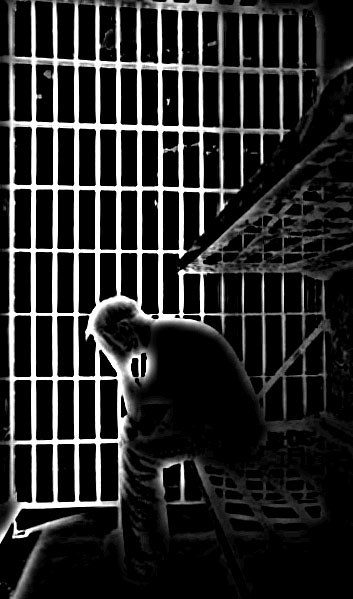

It’s hard to get a purchase on the reality of nearly two million people incarcerated in the U.S. on any given day of the year. It’s an American reality, and if it’s got two million people directly in its grip, how many more people become affected when their brother or father or son (it’s mostly males), their friend or cousin or coworker gets hauled off. There’s a ripple effect on other people that’s got to far surpass two million.

It’s hard to get a purchase on the reality of nearly two million people incarcerated in the U.S. on any given day of the year. It’s an American reality, and if it’s got two million people directly in its grip, how many more people become affected when their brother or father or son (it’s mostly males), their friend or cousin or coworker gets hauled off. There’s a ripple effect on other people that’s got to far surpass two million.

For the person behind bars, that’s part of the grief of it. Often, if they have young children, they feel the pain of them growing up without their father being able to mark their birthdays or see them learn to walk or start to play Little League. If he does get to see them, he’s shocked at how much they’ve grown and changed without him really knowing much about it. He’s become extraneous to their lives, even if he can talk to them once in a while on the phone. On the other end, inmates get the phone call that says a parent has died, but they can do little but fret on their bunk about not being there. Part of the prison experience becomes getting ripped from the fabric of a life you belonged in and from relationships that mattered.

Sometimes families wholly reject the inmate, refusing even to talk on the phone to them. They become shunned and abandoned.

Now, of course, this is all the outcome of karma, by which I mean, understandable, right in front of your nose karma, where said inmate acted illegally, got caught, and now pays the price: cause and effect. In general, people aren’t forsaken by their families without a lot of bad behavior leading up to that. Prison institutionalization puts up plenty of barriers to staying connected that go far beyond the razor wire, not the least being how inmates are moved around the prison system, and often they’re sent quite far from their home, making it hard for their families to go visit them. Then the inmate gets a number of years to stew in his grief about what he’s lost, what he’s separated from, and maybe most bitter, if he can get to it, what he’s brought upon himself.

Somehow that’s the most bitter thing of all. It’s easier if you can blame others for the misfortune of a prison sentence (and, after all, occasionally they really are to blame), and I think for a lot of felons, that’s where they focus. The people we work with, though, usually accept their own complicity in what happened. It seems hard to get to the dharma without that basic honesty.

If you were to ask me about the justice system, I would say, “Have absolutely nothing to do with it.” Once you’re sucked into the gears, it becomes hard to extract yourself. I’ve been recently corresponding with an inmate who had gotten paroled and been out about eight months. He’d started a regular civilian life, had fallen in love, and gotten engaged. Then, due to whatever legalities/technicalities involved, the justice system decided it wanted him back in prison for another four years. Now he’s in a Florida prison, utterly crushed that he may lose his potential for marriage and family, feeling suicidal, and drowning in the turn things took.

He’s waiting to hear about his appeal. What do I tell him?

Of course, there are way worse things than this that could happen, but I’m cognizant that it doesn’t matter to him so much where it falls out on the scale of suffering relative to other things. This is his existential crisis and the destruction of his fervent hope for a better life, one that was right in his hand. Well, that can happen to anyone. You don’t have to be in prison. But there’s a kind of karmic entanglement that takes place once you’ve got a criminal record that can cast a shadow over any happiness.

I’ve emphasized to him that he doesn’t know how it’s going to play out. We perceive things a certain way, solidify that into some monumental truth, then emote obsessively in a whirlpool of despair. Then it is hopeless because we’ve made it hopeless, and it is inevitable because we view it as inevitable.

So dealing meaningfully relates to the view you take. But where the rubber meets the road depends on a willingness to relate to your emotions meditatively. There’s no avoiding the grief, though prisons hardly provide a nurturing environment for feeling yourself to be that vulnerable. On the other hand, prisons sometimes seem to be built of grief, like grief constitutes the cement they used to bind the cinder blocks and erect the walls.

Grief, it seems to me, lends itself to spiritual alchemy. While it can trap you in the darkest kind of emotional sludge, it can function as a reagent for spiritual purification. It forces some giving up, a hard facing into loss. It comes with the collapse of your plans and your view of yourself. Avoiding grief usually fuels things like drug addiction, and the addiction becomes all-consuming vs. the reckoning that comes when you have to sit there with yourself and feel like a failure who let everyone down.

Meditatively-speaking–and here’s what I told the inmate on the verge of losing everything–one has to be willing to be with what’s taking place, however anguishing that may be. Instead of avoiding it, though, he stated that he hasn’t wanted to let go of this grief, that it would mean giving up and moving on, such that he sometimes can’t bring himself to go back to his breath. I told him that as soon as he felt a little less overwhelmed, then go back to your breath. At this point, at least, he doesn’t know how any of it will play out ultimately. Meditation doesn’t mean he has to choose one thing or another, one position or another. It means he has to open to what’s there, what he’s feeling now, and if that now is full of uncertainty, then it’s up to him to let it be uncertain.

If he can bring his emotional states into a meditative context, they can be felt, but they can move through as well. That’s where he might start to gain the insight that emotional states aren’t as solid as they seem, and he doesn’t need to avoid them and he doesn’t need to hold on to them. At that point, he might start to build courage and strength, while all the way through he’s going to need to find some compassion and heart, and understand he’s not the only one who has suffered devastating loss. Now he might really know what that means, and that’s where he might uncover his own wisdom.

That’s why, as bleak as this landscape can get (and I’m about to tell you a much bleaker story than this), genuinely suffering through your feelings can wake you up. An automatic potential for illumination comes forth, something you can find right there in the darkest, bitterest places.

I was sorting the mail recently, when I saw a familiar name next to an inmate number. He’d been out maybe five years. My heart sank. He was back in. He had been in and out before, most recently in solitary confinement where we exchanged a lot of intense letters. You know it when someone is really doing the work, applying themselves, and reporting honestly on what they have to deal with. He’d gotten out, had a girlfriend and seemed to get adopted into her family, and had been finding his way on the streets. I lost contact with him, as usually happens when released inmates get absorbed again into busy lives.

He’d lost his shit in a sudden, utterly blind rage at some irritating situation, and without even knowing the guy, started stabbing him with a knife. He also cut the guy’s girlfriend, when she tried to intervene. That he had cut a woman, he said, brought him back to his senses. Fortunately the man got timely medical care and survived. He got 15 to 30 years–essentially putting him back in prison for the rest of his youth, if not his life.

Here’s where you have to look more deeply at the karma. You see this with some felons. They become trapped over and over in self-created disasters. He’s now left to sort out something he can’t fully explain: why he even attacked that guy. He physically wounded two people, let everyone else in his life down, and now he’s back behind bars. This action certainly reflected a lack of meditative mind. With even a little attentiveness, he would have had some space around his angry reaction. That little bit of space could have given him a chance to think twice before doing what he did. But he had none.

So there’s the grief of living with the tormenting outcome of his own senseless actions, and beyond this, the need to understand what led to them. I told him that this was the main thing he had to come to terms with–what motivated that action. He thinks what happened was a trauma reaction, and I’m guessing that comes from his upbringing, such as it was.

But if you want to probe it even further: What put him into that particular family and circumstance? What brought him to a life where he keeps getting dragged almost gravitationally back into prison?

That’s the larger Buddhist perspective. Samsara itself, the endless wheel of repeating birth and death driven by karma, functions to imprison sentient beings. And beyond that, they can end up in an actual prison, if the metaphor isn’t getting through. That unbearable grief of having thrown away your life on something utterly senseless provides a chance to consider the chain of karmic events that keeps you in prison, either psychologically or literally. It makes for a path to tread on through the gloom that can lead you to revulsion for your own blind tendencies, a willingness to face yourself nakedly, and the pressing need to transform who you are.

Without this, it’s just more of the same.

The Wheel of Life

Glad you are still doing this work , Gary

Glad I did it for awhile

I’m on retreat with Tsoknyi Rinpoche in Crestone. 45 minutes from Buena Vista prison. Two different worlds; yet in the same world……..

They’re still in there, if you want to go back in and continue to help them….